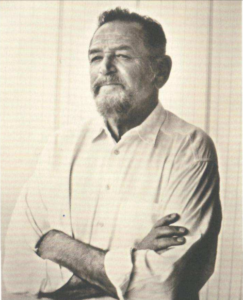

Richard Glazar – T2 prisoner

Richard Glazar, author of the book “Treblinka Station” was born on November 29, 1920 in Prague, in an assimilated family of Czech Jews. The turmoil of war first dumped him into the Theresienstadt (Terezin) – a ghetto founded in 1941 by the Germans. This place, which was often called a concentration camp by former prisoners, was depicted by the occupier as a model ghetto in which Jews had decent living conditions. For the purposes of the Red Cross’s visit to the Terezin ghetto, the Nazis recorded a propaganda film that arranged cafes and shops that did not exist on a daily basis. Only good-looking young people and children were selected for the recordings, most of the elderly was taken to other camps before recording the film, where they had no chance of surviving, e.g. to Auschwitz in occupied Poland. From Terezin at the beginning of October 1942, Glazar was sent to the Treblinka II Extermination Camp located in the General Government.

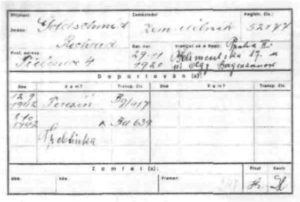

Richard Goldschmid’s (Glazar’s) transport document

Richard Goldschmid’s (Glazar’s) transport document

from Theresienstadt ghetto to Treblinka

This is how the author mentions the specifics of the camp:

One could use the term “masters and slaves” to describe all two-legged beings in Treblinka. But this term is only good as a slogan. Because in Treblinka it is not easy. There are bigger and smaller “gentlemen” here. Half-rulers, executioners commandants, execution masters and their helpers, living or semi-living slaves. And gravediggers – small and great…

“Wachman” – slave guards and executioner henchmen – are despised by both “masters” and execution masters, as well as by the cursed slaves. They are all young, around twenty, all are full of health and are characterized by vulgarity…

How will you recognize in Treblinka that you already mean something here, that you already have a face and a name? Simply after whether you can easily enter a workshop, preferably a tailor’s, “company”. Not everyone can get there to spend a little bit of time in their free time before nine o’clock to pretend the life..

At nine o’clock in the evening you have to put out the candles and everyone is supposed to lie down in their seats… Tomorrow I will throw the silk pajamas upstairs, which I took from the bedclothes and I am wearing now. After three days, or rather three nights, it is dotted with bloody spots from fleas. Maybe tomorrow I will bring a new pajama in advance … Maybe my pajamas have not reached Treblinka yet, maybe they are still on their way. Or maybe tomorrow I won’t need it anymore…

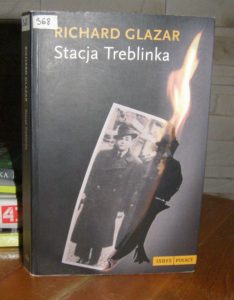

Richard Glazar, Stacja Treblinka, Warszawa 2011.

Glazar worked in the camp in the commando dealing with sorting things after the murdered. He survived the hell of Treblinka and escaped from the camp after the uprising that broke out on August 2, 1943. He was in a group of several dozen people who managed to escape.

He was one of the few who managed to survive in the camp for so long, almost throughout the entire period of its operation. He brought four diamonds from Treblinka that helped him to survive and prove the world about the horrors he faced. He talked about Treblinka many times, participated in the trials of criminals as a witness. He was very credible to the Court because he gave his testimony without unnecessary emotions and although he charged individual defendants, he spoke positively of some. He showed that he did not burden the torturers because of hatred, but because of real crimes. Richard Glazar was known for his sense of humor and was a great husband and father. Experiences from Treblinka left him with its mark, which he struggled with for the rest of his life. When his wife, the largest support, was missing at his side, a week after her death, in December 1997, he threw himself from a window on the fourth floor in a senior’s home in Prague.

In his book “Treblinka Station”, Richard Glazar takes the reader to the camp reality. It allows, at least partially, to understand what was happening in the Extermination Camp Treblinka II.

Ilona Flażyńska

Pictures from Richard Glazar’s book Stacja Treblinka, Warszawa 2011.