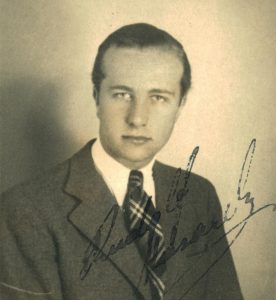

Rudolf Masarek – więzień T2

Rudolf Masarek was born on September 10th, 1913 in Prague, into a wealthy family of tailors. His younger sisters were: Katuša Masarková (born on September 26th, 1915) and Eva Masarková (born on September 27th, 1924). As the eldest son of Ida Masarek and Morič Masarek in 1931 he inherited the business Egerer & Masarek in Prague after his late father. The company specialized in textile industry, producing ties and cravats (men’s scarfs).

On March 16th, 1939, on the Czech lands which were under the Third Reich occupation, the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was created under the leadership of Emil Hácha. Masarek’s property was confiscated due to his Jewish background, while he and his wife on August 10th, 1942 were sent to ghetto in Theresienstadt. It was located in a fortress from the turn of the 18th and 19th century, by the Ohře River, on the southeast of Litoměřice. After spending almost a month in ghetto Masarek left Theresienstadt as a number 415, on a transport marked with symbol “Bu”. His journey began on September 19th, 1942 and after two days he arrived in German Nazi Extermination Camp Treblinka II. He came with his wife Gisela Masarek (born on April 18th, 1923), number 416, who was in advanced state of pregnancy. His wife had no chances of surviving, however Rudi was immediately noticed by SS-Manns. He stood out in the crowd – he was dressed fashionably and had Aryan appearance: blue eyes and blond hair. He had a great body shape thanks to swimming and fencing. It was probably his appearance, that gave him a chance of survival in the camp.

Masarek was assigned to sorting clothes; due to his impeccable attire, the executioners were sure that he would be able to handle this task perfectly. He had to face a new reality, a cruel one. With his style he wanted to express a will to live, show the he won’t let anyone break him. The elegant outfit which helped him stand out among other prisoner gave him motivation to survive the next days. He was giving advices to his fellow prisoners regarding clothes selection, thanks to him they were wearing the best quality clothes, which were fashionably matched. All this caused that the Czech prisoners were treated better by oppressors.

During his stay in Treblinka, due to the incorrect spelling of his surname, he was identified as a member of the family of the first president of Czechoslovakia – Tomáš Masaryk. Rudolf did not bothered to correct this mistake – this rumor also helped him to survive for about 10 months in the German Extermination Camp.

The deputy commander of the camp Kurt Franz trusted him so much that Rudolf was allowed to take his dog Barry for a walk.

Masarek, as a lieutenant of the Czechoslovakian Army, joined the conspiration which was preparing the revolt in the camp. Organizing an armed uprising in the camp realities was very difficult. It was necessary to acquaint the right people who would not reveal their intentions to Germans. There was also a matter of acquiring weapons, the whole action plan and the distribution of tasks among individual people. Despite many inconveniences, all objectives have been accomplished.

In the accounts of prisoners, who survived the revolt in the camp appears information that Masarek was very agitated on the day of the rebellion. He knew that he will stay in the camp till the end. He wanted revenge for the death of his family. He said his goodbyes to his fellow prisoners. Rudi’s task was to shoot up the Ukrainian barracks from the nearby dovecote, where he had a gun hidden. According to the relation of Stanisław Kona, during the shooting he was shouting: “This is for my wife, my child that did not see the world yet, and this is for the humiliated humankind”. Thus, he gave vent to his emotions.

His mother received certificate in Czechoslovakia that he died on September 2nd, 1943. It was the day of the rebellion in the German Extermination Camp Treblinka II.

A fragment of the quoted account was taken from: Wójcik M., Treblinka 43, Warszawa 2018, s. 193

Photographs come from the book by Richard Glazar, “Treblinka Station” and the website holocaust.cz

Translation: A.D.