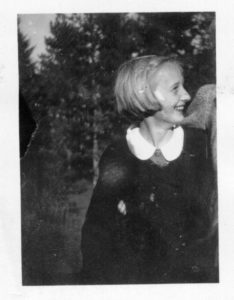

Hania Zaleska - T1 Prisoner

She was the youngest child of Lucyna Natalia née Roman and Teofil Zaleski. She was born on 30 April 1930 in the Drozdówka estate, located in the Siennica commune, Mińsk Mazowiecki county. She had six siblings: sisters – Irka, Basia, Janeczka and Terenia as well as two brothers – Bogdan (who was dead at the time of her birth, but the memory of him was always alive in the family) and Roman.

She was the youngest child of Lucyna Natalia née Roman and Teofil Zaleski. She was born on 30 April 1930 in the Drozdówka estate, located in the Siennica commune, Mińsk Mazowiecki county. She had six siblings: sisters – Irka, Basia, Janeczka and Terenia as well as two brothers – Bogdan (who was dead at the time of her birth, but the memory of him was always alive in the family) and Roman.

In 1939, when World War II broke out, Hania was 9 years old. For two years, she lived in the Bachorza manor located in the Sokołów Podlaski county, together with her whole family. From September 1937, also for two years, she and her older sister Terenia attended a primary school in Sokołów Podlaski.

As the youngest in the family, always cheerful and smiling, extremely agile, she was the favourite of the whole family, not only the closest one, but also of all aunts, uncles and cousins. She was the “apple of our eye”. She herself had the closest relation with her almost two years older sister Terenia. They were always and everywhere together. They were never seen separately and they could not even imagine that it could be otherwise. When they went to school, they could not get over the fact that they did not sit not only at one desk, but not even in one classroom.

During the occupation both girls stopped going to school in Sokołów and started to be schooled at home. At that time, the compulsory schooling was not observed, and besides, mainly manual labour was taught at school, which was in accordance with the doctrine of the occupation authorities that did not want to allow Polish children to be educated. I do not have the slightest doubt that teachers tried to pass on the normal school curriculum to students, but it involved such a high risk that our parents decided to protect the youngest children from it.

In 1941, Hania experienced a great drama, which she could not cope with for a long time, despite the fact that she was given the most heartfelt care. It was a tragedy for the whole family. Hania’s beloved sister Terenia died of acute pneumonia in March that year. Half a year later, in September, her mother died, who had been fighting cancer since the beginning of the year. Hania found it difficult to understand all this, and even more so to accept it. Broken by this experience, she moved around the house as if not noticing what was happening around her. It took a long time before she returned to a certain balance and started taking part in the normal life of the family again. She also started learning with passion. She confined that she wanted to learn in order to be able to help people who, after all, should not become terminally ill. She wanted what she was then saying to become our secret only.

In 1941, Hania experienced a great drama, which she could not cope with for a long time, despite the fact that she was given the most heartfelt care. It was a tragedy for the whole family. Hania’s beloved sister Terenia died of acute pneumonia in March that year. Half a year later, in September, her mother died, who had been fighting cancer since the beginning of the year. Hania found it difficult to understand all this, and even more so to accept it. Broken by this experience, she moved around the house as if not noticing what was happening around her. It took a long time before she returned to a certain balance and started taking part in the normal life of the family again. She also started learning with passion. She confined that she wanted to learn in order to be able to help people who, after all, should not become terminally ill. She wanted what she was then saying to become our secret only.

As the threat to her family grew due to the growing terror, she calmly and even with a smile took over household duties to relieve those who, in her opinion, were more at risk. She also said that she had to be educated in this area as well. However, she was never drawn by us under any circumstances into any underground activities in which other members of our family took part. Nevertheless, I had the irresistible impression that she watched very carefully everything that was going on around her and that she drew only conscious conclusions from it.

I became confirmed in this belief after returning home, when I talked to her close peers (friends). It turned out that they were preparing themselves together to undertake some unspecified auxiliary activities for people working in the underground. Fortunately, it was still very naive and childish.

In 1943, I, Irka and our father were arrested by the Gestapo. Hania accepted the news with peace of mind, but also with anxiety. With a trembling heart she also thought about the earlier departure of Romek and Janeczka, who had to hide. She was also very happy when we were released from prison after 3 months. However, she continued to be tormented by anxiety about the fate of Janeczka and Romek. She never saw them again…

At the beginning of 1944 our family home practically ceased to exist. The Germans searched for Irka, Janeczka, Romek and our father for underground and partisan activity, and they had to hide. Only two of us stayed at home – Hania and me. The so-called Treuhaender, the official trustee – the commissioner managing the property taken over by the German authorities – came to the manor.

In the first days of July the Germans occupied our house as quarters for the army returning from the eastern front. They left only three rooms for us. Then I immediately contacted a liaison officer known to me and sent a warning to the underground groups operating in the vicinity that a large German unit had taken over the house. It was necessary because the road from Drohiczyn by the Bug River to Sokołów, which ran directly next to our fields and at the exit of a well-wooded entrance avenue, were often passed by armed partisan units or other underground units, such as liaison officers, intelligence officers, distributors. They often stopped in the avenue to make reconnaissance or last preparations for the action.

I never managed to find out whether the liaison officer failed, or whether the information provided by me was ignored, or whether it did not reach all units.

Suffice it to say that one night the armed “warriors”, as the Germans called them, suddenly came across a German patrol holding a guard in front of the house. Heavy shooting broke out. Poles supposedly withdrew without losses, but two German soldiers died in the shooting. The Germans accused us of cooperation with the attackers. There were no grounds to make such an accusation to us. I suppose that it was just a matter of retaliation. From the moment the Germans arrived, we were not allowed to leave the house without their knowledge and consent. When we were going to the city, we were always accompanied by one of the stationed soldiers.

That night we slept as usual in two opposite rooms, separated by a small corridor. We were forbidden to leave the house and after entering our bedrooms we were locked there. A soldier was keeping guard the whole night in the corridor. Under the windows, guards were walking from both sides of the house. We had no possibility to communicate with anyone from outside, and at night also with each other.

Early in the morning we were transported to the prison in Sokołów. Hania was 14 at the time, I was 22… After our arrest and deportation, our house was left without any protection, wide open, and nobody from the family knew yet about what had happened. However, I found out confidentially, already in prison, that my parents’ friends immediately made efforts to make contact with our father, and at the same time, they started to make strenuous efforts to free us. Supposedly, a large amount of “hard currency” was even offered to the Germans, coming from the gifts of our neighbours. When the efforts to free us both failed to take any effect, they tried to free at least Hania, who had not been convicted. Unfortunately, these efforts were ineffective.

During the interrogation I was informed that I had been sentenced to death. I asked what would happen to my sister, who is still a child and had nothing to do with the case. I was answered calmly that the “noble and honourable German nation does not kill children”. I asked for her to be released. In response, I heard that “time will come for this”. That was the end of the interrogation.

Ten days in prison in Sokołów passed in extremely dramatic circumstances, because the Germans, who were already partially withdrawing, hastily liquidated their cases, as well as people. We knew that all administrative units taken over or created by the Germans (mayor’s office, arbeitsamt, hospital, post office, etc.) were being liquidated. The official documents, various types of materials, including sanitary ones, were packed and burnt or taken away. People were liquidated in the literal sense of the word – they were convicted people, often even only suspects, as well as informers. The latter are said to have been liquidated all. There was a clear sense of hectic rush, often turning into mere turmoil. The roads were crowded by retreating troops and civilian workers leaving with Germans or fleeing from the incoming Russians. We received worrying news of such moves of the occupants, such as burning down the prison in Małogoszcz with all the prisoners, gas poisoning the prisoners in some other prison and the like. For the last few days, at dawn, single people or groups of prisoners consisting of several to a dozen or so people were taken out and they have never come back again. According to the guards, they were liquidated in the nearby forests on the road leading to Siedlce.

Among them was a group of 14 Ukrainian girls returning from forced labour in Germany. They were brought to the prison in Sokołów 3-4 days before its liquidation. They were cheerful, laughing, and all evenings they sang their Ukrainian dumkas. I do not know why they were executed. The guards said that the Germans accused them of prostitution.

In the morning of 20 July 1944 we were loaded onto a truck with a group of 39 prisoners. The prison in Sokołów seemed to be completely empty. All entrances, including the entrance gate, were open. Hania was concerned about all this and only looked at me questioningly. I tried to raise her spirits and calm her down a little. I had the irresistible impression that she was afraid that they would take us to some forest to shoot us there. I hugged her strongly to myself and said, Don’t be afraid Haneczka, whatever happens to us, we are together and I will always hold you in my arms. She looked at me with gratitude and even trust. She tried to make a pretence… She comforted me and asked me not to worry.

We didn’t know where we were being taken. When we passed a town (later I found out that it was Kosów Lacki), we all heard and felt some strange sound coming out from under the wheels of the car we were driving in. It was hollow, with rhythmically falling and again intensifying rumble. It was also accompanied by rhythmically repeating vibrations. Someone among the prisoners said in a muffled voice: yes, we are close. I didn’t know what was to be nearby, but it all seemed so ominous that I can’t forget it to this day and I’ll certainly won’t forget it to the end of my life. Much later, already after the war, I found out that these noises were caused by concrete footings, evenly distributed on the newly-built road to the artificially created desert – the death camp, hidden among forests. Whenever I take this road today, I still hear this terrible rumble.

The Treblinka camp welcomed us with an ominous inscription “Arbeit Macht Frei” and an equally ominous briefing carried out by two Czech Jews under the supervision of Ukrainian guards and Germans. After rummaging through our all too modest bundles, they asked us to make sure that we did not have hidden bread, paper, pencils or other markers. They informed us that if they found any of these things or anything that was forbidden to have in the camp, we’d be “punched in the face”. None of us had such things, or at least they were not found on anyone of us. This is how the last stage of our tragic journey began. For Hania, unfortunately, it turned out to be the last stage of her life journey.

Stay in the camp was a nightmare, which we had already heard about before we were arrested, but the reality was incomparably more terrifying than we could have imagined before. Hania said she felt as if she was living in an unreal world or in an awkwardly terrible dream.

From the very beginning we felt a painful foretaste of our stay. When we left the bath house where we all washed together and were dressed in camp clothes, we had to run quickly to the barracks in one row. On our way stood “our guardian”, an SS officer with a whip in his hand, with which he greeted every passer-by in a very meaningful way. He was a young man in his twenties. Actually, he looked normal. I suppose that he was not much older than me and I couldn’t understand why he treated us – people just like himself – the way he did. I wanted to protect Hania from such a welcome, and also to take a closer look at him to understand why he did it and I didn’t run as fast as my predecessors. I stopped in front of him. I thought that if he had to beat someone, let him beat me, and then Hania, who was just behind me, might be able to walk calmly. To my amazement he didn’t hit me. He quickly got on his bicycle, which he always used to move around the camp, and left. I was relieved when I saw Hania smiling shyly at me.

Hania quickly became immune to the external living conditions in the camp. She seemed not to pay attention to the dark barracks without windows, in which dozens or even more than 100 people cooped up in one undivided space. The constant noise of their subdued conversations, their constant anguished whispers, muffled groans and sighs created an atmosphere of depression, horror and despair. In crowded, dirty barracks, there was no way to sit normally – you could either stand up or sit half-bent on the bunk beds, which were stacked low one above the other. Nights, when it was allowed to lie on bunk beds, also did not give a real rest. Hard, tight and creaking beds, fleas, torn, stiff and dirty blankets did not allow for normal sleep. Rigid and dirty clothing in which we were dressed, and which could not be exchanged even for the night, also made it even more difficult. These were uniforms and underwear of the fallen or murdered soldiers and Soviet prisoners, with even the traces of blood unremoved.

Hania did not want to sleep on a separate bunk. She was always lying next to me and cuddled herself to me helplessly looking for some kind of soothing and support. It wasn’t the worst thing yet. Much more pain and suffering added to our constant anxiety and humiliation, which we all experienced at every step. One of the most unpleasant experiences was the use of toilets. They were on a slight hill. These were simple deep open holes covered with several poles and possibly branches thrown after each use. It was difficult to go there alone, above all because of the proximity of the roads and paths that prisoners and, of course, the guards had to walk along. Right next to us there was also a camp for the Germans, separated from our toilets by barbed wire. At least the two of us had to go there to provide ourselves any protection. In this camp the Germans were punished for desertion, insubordination, or for the so-called different attitudes, namely ordinary stupid garrulity, of course mainly politically uncensored. At the time when I was there, there were few of them – probably only a dozen or so people.

Our constant anxiety, worrying and nerve-racking, was additionally intensified by the daily executions of prisoners chosen mainly from our group and from among the Jews. The first batch of 11 people from our 41-person group was executed on the first day immediately after our arrival in Treblinka. Later, the groups of people who were executed were less numerous. None of us, however, knew who would be next. It happened that in the middle of the night the camp lights flashed and we saw that one person was led out, or maybe it was a small group, which was supposedly led to the execution site. Then it seemed to us that we could hear shots and then the lights went out. I think that on purpose, in order to intimidate us, drastic rumours were later spread among the prisoners about how the prisoners perished and died.

We were particularly shocked by the tragic fate of two victims chosen from among us. They stayed with us in a prison in Sokołów in a neighbouring cell and came with us to Treblinka. She was a charming 35-year-old woman, a research worker at one of the universities and her 11-year-old daughter, cheerful and confident. I talked with this lady several times in Sokołów. She told me that they had been arrested because her husband (her daughter’s father) was a Jew or a half-Jew. I don’t know what happened to him. I’d never seen him. Some prisoners, with whom he was supposedly in one cell, said that he was executed here on the spot. They were separated from him and then transported together with us to Treblinka. His daughter missed him very much and was worried about him, so her mother told her that he had been sent to Warsaw to settle some important matters. The girl complained that she lacked a daily knocking of their daddy on their cell with a question about how they felt and assurances that he loved them. She boasted quietly that they had a special way of communicating with each other by knocking. Both were executed in a particularly brutal and cruel way, especially for the child, in the second or third group of murdered prisoners.

I knew most of the people who had been deported with us to Treblinka only by sight. Some people have been preserved in my memory as unnamed figures, and I remember the names of others.

For example, I remember a couple of very nice young people in love with the most beautiful young love. Her name was Laura and she was a charming 22-year-old girl displaced from Poznań. His name was Krzysztof. He was a beautiful boy, a few years older than her (reportedly he was the son of the director of the power plant in Sokołów). I had known their surnames, but I don’t remember them anymore. They had to die in the most beautiful years of their lives. We often talked furtively and I never noticed anxiety or despair in them. Laura had a commemorative gold medallion with an old family photograph of her grandparents or perhaps great-grandparents. She asked me to keep it for her, and if I manage to leave, I would give it to her family. Of course, I couldn’t promise her that because we were both in the same situation – sentenced to death. We agreed that if she was first selected, I would collect the medallion from the person she had indicated who did not have a death sentence. This combination failed because all three of us were in the last group of 19 convicts.

After my return home, when I found myself in ravaged Bachorza, I was visited by Krzysztof’s desperate parents. They already knew about the course of events in Treblinka, but they begged me to give them at least a shadow of hope that their son was alive. I couldn’t do it. However, seeing their enormous despair, I only said that although everything is possible in life, the probability that Krzysztof survived is extremely low.

We also witnessed with Hania an armed effort of the last Jews still living in Treblinka. Contrary to what has been said so far, that all the Jews from the Treblinka camp died in the gas chambers and crematoria long before our arrival, it turned out after our arrival that it was not entirely true. Although the gas chambers and the crematorium had been liquidated by the Germans earlier, a handful of Jews still remained in the camp, the number of which increased from time to time by people still being captured here and there. At the moment of our arrival in Treblinka they were there for sure. According to the information of Polish prisoners who had been in the camp for a long time, there were about 200 of them then. However, they were mainly Jews from outside Poland, including Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Belgium and France. These were groups of Jews deported from these countries with whole families, whom the Germans promised resettlement in other countries with a lower population density and good living conditions. They also ordered them to take all their property with them, ensuring that it would be transported together with them and returned to them at the place of settlement. I found out about the wealth and size of the property that had never been returned to them when one day I was sent to work in the barrack where they were stored. My job was to segregate these things according to their wear and tear as well as value. The barrack was very large. It was filled with shelves and crates, in which there were neatly arranged items of high material value, and often, as it seems to me, also artistic value. Some of them were still lying on the floor.

In Treblinka, the Jews were put in several barracks located closest to the farm buildings of general use. They lived in much better conditions than Polish prisoners because they were allowed to use the basic part of the brought property. They were employed on a camp farm, in a dairy, butcher’s, car repair shop, etc. Among them there were many good professionals – mechanics, electricians, watchmakers, whose skills were willingly used by the Germans. However, all this did not give the Jews peace of mind. They found out quite quickly that they had not been brought here to settle.

I don’t know how many of them remained after the mass pogroms of 1942 and 1943 and how many more were brought since then. I also don’t know when their executions began again. When I found myself in Treblinka, I had already witnessed at least some of them being led out almost every day. They never came back… So the others knew, or at least could have guessed, what fate would happen to all of them. Probably they didn’t want to wait for it idly.

Supposedly, through the Polish prisoners transported daily to the railway station in Małkinia to load and unload wagons, the Jews got ahold of weapons. There was not much of it and it was quite poor, but it was enough for them, however, to try to free even a few people. I think it was 24 or 25 July. In the afternoon, after the return of the prisoners from Małkinia, the Jews locked themselves in one of the barracks and waited for the Germans, who were to take out the next victims to the execution site. When the Germans approached, the shooting began. Polish barracks, which were nearby, were immediately surrounded by Ukrainians and Germans. The Germans, apparently intimidated, ordered us in an unexpectedly “friendly” way to go inside immediately (for our own good) and under no circumstances to leave, not to stick heads out and not to look out. They assured us that if we obeyed them, nothing bad would happen to any of us. They set up a few armed guards next to our barracks. All the others surrounded the barrack, where the Jews hid and defended themselves. Continuous shooting, but not very intense, lasted until dusk. Later we could only hear single, sporadic shots. We looked out of our barracks and stuck our heads out despite we were told not to. However, we saw only attacking Germans from our female barrack. Male barracks were closer to the Jewish ones and the prisoners in them certainly saw more. Later on, they quietly told us that the Jews were bravely defending themselves and after the Germans entered their barracks, they hid in the attic and defended themselves there to the end. They did not give up. They supposedly killed a few Germans, but I don’t know to what extent this information is true. In any case, however, the confusion and feverish running about of the Germans indicated that this was indeed the case. This event gave encouragement to other prisoners. A little more encouragement was given to the prisoners by other events that took place at about the same time. At first, these were parcels handed over by the Central Welfare Council to the prisoners, which were not only accepted by the Germans (which they supposedly had never done before), but also unexpectedly distributed to the prisoners. However, what was even more uplifting was the allied overflight. We all saw it very well – it was in the evening on fine last evenings of July. We all ran out of the barracks and looked at them with genuine courage and hope. Germans didn’t react to it as if they hadn’t seen anything. However, it was already 30 July. They dropped leaflets informing that the day of our liberation is approaching, so that we wouldn’t lose our hearts and try to hold on. These were the last encouraging events during the last days of the camp’s existence. However, they were encouraging only for those who hoped to be released. Both me and the group of 18 prisoners who remained after the executions, we had no great illusions about our fate. We were all sentenced to death and we knew that the Germans would not pardon us.

I was glad that Hania was to leave the camp soon. However, I felt some anxiety in my heart, because already 3 days earlier, on 27 July, unexpectedly for me – I remember that day well, because it was the day of our Mom’s name day, which we always celebrated with due ceremony – Hania came up to me after the roll call, took me by the arm, cuddled up and said very quietly: Basia, you will soon be released from the camp, but don’t worry and don’t cry that I’ll stay here forever. I can’t say even today how surprised I was and shocked by this statement. I didn’t believe it even for a moment, of course, but my heart sank at the very thought. I realised how this child – my youngest little sister, whom my mother entrusted to my care while dying, because she knew how much I loved her – how she had to suffer and what she had to experience, that she came to such a conclusion. Even today, 60 years later, I can’t calm my heart and think about it without pain and tears.

Unfortunately, that cruel day came – 1 August 1944. Russians were coming, Germans were withdrawing in a hurry – they were running away. However, they did not abandon their cruel practices.

Already the previous day they returned our clothes taken away from us after the briefing. They announced an earlier than usual morning roll call. Before that we had not all seen each other together. Men and women were taken to work separately. What is more, we never met prisoners taken to work in Małkinia, or those working on the camp farm. It was only at this last roll call that I saw how many of us there were.

The morning of 1 August 1944 was cloudy and gloomy. It was constantly raining. We were ordered to stand in a certain order. First there were men in many long rows, behind them stood women also in long rows, but not so numerous. There were already Germans standing in front of the rows. The camp commandant with his entourage, namely with the commanders of individual sectors and barracks as well as the armed guards (Germans and Ukrainians) standing a little further away. Gestapo officers from Sokołów and supposedly from Małkinia and Wyszków stood on both sides of the commandant. The leader of our sector – an SS officer (I think his name was Stormke, but I don’t know if I remember well) started a “fatherly” speech on behalf of the commandant, addressed to all prisoners. He said something like that our stay in the camp ends today. They – our “guardians” – hope that our stay has served us well, taught us a lot, which we will be able to use in our lives for the good of us and our society. He wished everyone that this would happen, because it would ensure our prosperity and peace. Finally, he said that now we should disperse calmly and in order, and that we can return to our homes and families, or wherever we want to go. We are all released at the very moment, with the exception of 19 people who will remain to put the barracks in order. These people will be called up from a list and will go out one by one and put themselves in order in front of the rows.

And he began to read the names. Hania was called out as the first one. Since I was always second on the list, I took Hania by the hand and without waiting for the further reading I started to go out, hoping that I would squeeze Hania in somewhere in the dense rows of men standing before us. At that time, the officer was further reading out the names that I didn’t listen to any more, but among which supposedly my name was not read out. I don’t know and I never found out if this was the case. But somebody quickly realised it and immediately a few people stopped me saying frantically: what are you doing? Stop immediately! Do you want to make them angry, so that they could shoot and kill us all! They will read you out and then you will go. I was completely confused and stopped for a second holding Hania by the hand. It lasted a fraction of a second, but during that time they separated me from Hania by force. Some guards ran up and pulled me out of the row because I must have disturbed some of their order. I tried to get out of all my strength and run after Hania, but they didn’t let me go, and Hania was pushed in a different direction. There was a terrible commotion. Some German shouted “Ruhe”, another one fired into the air, and in the meantime the rest of the chosen ones were coming out and they were surrounded with a cordon of German and Ukrainian guards. Someone from the prisoners said, They haven’t noticed yet that you haven’t stepped out. Someone threw a large rustic scarf on my head and pushed me into a feverish, already mixed crowd of other prisoners. Now I don’t remember much, but even then I didn’t realise what was happening to me. I was surrounded by a crowd of chaotically running people (I think that there were several hundred people there), which was moving quickly towards the exit gate. Further rows were pushing rapidly on those going forward. Everyone wanted to get out of that turmoil as soon as possible, all the more so because the guards at the back let us know about themselves again, who screamed “Schneller, schneller” and started shooting again… probably in the air to spread fear. Gestapo men stood quietly at the gate with their hands on the holsters and watched the confusion carefully. When I found myself behind the gate, I decided to wait for the pushing crowd to pass, return to the camp and find Hania. They didn’t let me in. They probably thought I was crazy because I was wandering in despair like a crazy one to get back. Someone told me to wait quietly until everything calms down because there is still a lot of work in these barracks and I will manage to get there. Because it was still restless in the camp and the Gestapo were in a frenzy, someone took me by hand and said calmly that I should go with other women to hide from the rain in a nearby village and wait there. They also promised me that they would be vigilant that we wouldn’t get lost with Hania.

I don’t know and I never found out what happened next. When I realised that I was in a cottage, that I was lying on a hard bench covered with a dry, self-made bedspread with a small pillow under my head, someone told me that I had no reason to go back to the camp because nobody was there any more. The Germans got on the previously loaded cars and hastily left the camp area. I didn’t understand what it meant then. I couldn’t imagine it.

And I still don’t know how it happened that on the third day after leaving the camp I found myself in Sabnie at Mr and Mrs Moniuszkos – friends of my parents and at the same time the parents of our schoolmates (from the gymnasium in Siedlce). I remember, however, that when I saw them, they asked me where Hania was. I didn’t know where she was and I don’t know what I answered.

What happened next was just my personal tragedy.

Barbara Bednarska née Zaleska, Hania’s sister