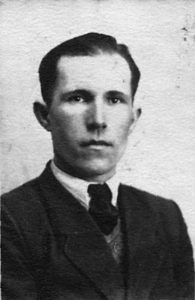

Antoni Tomczuk - T1 prisoner

ANTONI TOMCZUK

Memoirs from the Nazi Labour Camp in Treblinka

Part I

On 10 June 1943, at dawn, between 2:00 a.m. and 5:00 a.m., the Germans surrounded our village of Sabnie and the manhunt began. Germans walked from house to house and turned out all men outside the commune. The village was tightly surrounded by the army, and machine guns were placed on the street. That morning an inhabitant of Kolonia Stasin, Władysław Romańczuk, was walking to our village by accident. The Nazis also stopped him and he had to join our group. In front of the commune, in the presence of the village leader and frightened families, we were packed up onto a truck and transported under escort to Sokołów Podlaski, where we were led into a building. We waited there for several hours. There were about 50 of us, including one woman who did not want to leave her husband. There were also a few more displaced people from the Poznań province, who lived in our village, and with whom we shared our misery. They were very good people. I became particularly friendly with Kazimierz Wietrzyński who came from the village of Borzykowo near Września. Germans also took my cousin from Warsaw, Lucjan Rasiński, who lived with us during the war. After a few hours we were loaded onto a truck again and transported under escort. We didn’t know where we were going. We were taken to some place and after leaving the car it turned out that we were in Treblinka. Above the gate there was a large inscription. We were in the camp. On the camp square, they placed us in line and ordered us to put out all our possessions, even the smallest items, including what mothers had given us for the road. One of the Ukrainians was searching us, walking at the front, and the German, as I learned later, it was Szwarc, followed behind him with a nagaika-whip ended with lead. At one point the Ukrainian found two grosz in one of the deportees’ pocket, an elderly man, Mosiej. This man did not even know that he had them. The Ukrainian pulled out the coin and showed it to the German, and he hit Mosiej with the whip on his head. A blue ridge appeared on his face and we had the impression that the guard knocked out his eye. After the search we were told that if we escaped and were caught again, we would be shot dead. This was the fate of a prisoner who was caught while trying to escape. In the evening we saw him being brought, and in the morning, going to work, we saw his body lying at the gate, for show. The Germans also told us that after our escape the whole family would be shot dead and the buildings would be burnt down. Then we were led to the barrack, where we lived for the rest of the time. The barracks stood in line, they were wooden and covered with tar paper. There was only one entrance – from the roll call square direction. In the middle of the barrack there was a corridor, the whole bottom was concrete. On both sides of the corridor there were wooden bunk beds for sleeping. Prisoners slept on bare planks. After being shown the barrack, we were turned out again to the square. It were still two hours until the evening. At the beginning we were ordered to carry soil from place to place on the wooden barrows, four to the barrow, which took place under the supervision of drunk Ukrainians. In order to keep us under control and enslave us, we were tormented until the evening.

The food in the camp was terrible. Each day was similar to the next one. At the beginning it was very difficult to get used to. When they wanted us to become weak as soon as possible, they gave us meals that practically nobody ate. Breakfast was about 6:00 a.m. – 7:00 a.m., and it consisted of a bowl of soup, dirty salty water with some bran without the smallest slice of bread. After such a meal we were terribly thirsty, because we didn’t get anything to drink. Prisoners had nothing to quench their thirst with. At noon there was dinner – a similar portion of soup with a potato, often rotten, unpeeled and sprouted. In the evening, before sunset, supper – one slice of bread, sometimes with the addition of margarine or beet marmalade and a bitter liquid, reminding coffee. There were two Kapos in our barrack: Jóźwiak and Zajferd, responsible for order in the barrack. They also took part in roll call meetings in the morning and evening, when the state of the barrack was checked. Kapos had nagaika-whips and were arrogant towards us. Sometimes they even beat their fellow prisoners. They did not work themselves and slept in a separated place at the front of the barrack, at the entrance. Bowls and spoons, with which we ate, were also stored at the barracks entrance. We ate all the meals on the square in front of the barrack. On the camp grounds in front of the barrack there was a roofed lavatory-latrine, where one sat on a pole, doing physiological needs. As I realised after a short time, the whole camp was very well organised – in the German style. The whole camp was fenced with a 2 metres high double barbed wire fence, two watching towers at the corners of the camp, as well as posts at the entrance gates. The part of the camp intended for utility purposes consisted of several barracks of various sizes. Then there was a Jewish barrack, followed by our barrack – for Poles, and another one for women. Then there was a sorting area and other structures. Our barrack was separated from the Jewish and women’s barracks with a barbed wire fence. There was also a farm in the camp, which consisted of stable buildings. They bred cattle, pigs, sheep and three pairs of horses for work in the field and camp transport. The manure was taken away with a water cart pulled by a small horse – a pony. Additionally, there were also a dairy and a bakery on the camp grounds, as well as administrative buildings to serve the Germans and Ukrainians. I remember that turtles were kept next to the dairy, next to the passage to the barn, in a concrete small pool. On the grounds of the camp, all farm work, such as kitchen service, weaving, shoemaking, saddlery workshops, dairy and bakery were operated by Jewish men. Their wives and even children were settled outside the camp in Kolonia Milewko, where Jewish women ran a laundry for the entire camp staff. Sometimes I used a horse-drawn cart to take meals for these women from the camp kitchen. On Sunday, the Jews serving the camp received passes to their wives in Milewek, from where they returned to the camp in the evening. At the beginning of my stay in the camp I worked in the middle of the camp, doing various jobs on a farm. First, the Germans didn’t let us out of the fenced area of the camp. This situation lasted a week or two. After this “quarantine” we started to work in the gravel pit, loading gravel onto wagons. There was railway leading to the gravel pit – a railway track used by the locomotive to drive out the wagons. After being filled, they were taken away somewhere.

Part II

The work in the gravel pit was supervised by Ukrainians who walked on the slopes over the excavation. They sometimes called out a prisoner, a Jew, and pushed him down for fun. As a result of such a fall, the unlucky man broke his arms and legs. The work in the gravel pit was murderous. The middle of the summer – scorching heat, no water to drink. People working in the gravel pit looked like skeletons: bones covered with skin. I worked for about a month in the gravel pit. In addition to manual loading, the “Bagier” backhoe loader was used to load the gravel onto the wagons. Farmers from the village of Guty delivered water for this excavator’s engine cooler. They did it one by one by order of the village leader. One day, one of the inhabitants of Guty, Roman Ryciak, brought water. He had parcels for us from our families (our families did everything to get some contacts and help us) under the seat of the cart. When we saw that Ryciak had parcels for us, we quickly pulled them out. It was seen by a German and a Ukrainian. As a punishment, Ryciak was imprisoned in the camp. His horse – a bay mare – was taken away from him. At that time, normal field work was carried out on the farm, where two Czech Jews: Arun and Gustaw worked with horses. There was also a third Jew from the Sokołów county who fled. For this reason a problem arose – who to employ for horses. Gustaw and Arun advised the German farmer, Roten Fir, who would be suitable for this work. The Jews pointed me out, because I used to help them sometimes. I got two mares: chestnut Berta and a bay one, which the Germans took from Ryciak. This work turned out to be a real stroke of fate. I could enter the barn, where potatoes for pigs were steaming and eat steamed potatoes there, and even before the evening, when I was escorting horses, I often hid some potatoes in coat-tails and carried them to the barracks. We suffered such a terrible hunger that these potatoes became a real delicacy. One time this was noticed by the German farmer Roten Fir. I thought he would kill me there. I stood still and thought it was the end, but when he saw my fear, he only said: Polnisz essen, essen. I think only he had a human soul among those torturers. Work horses were always fed and dressed by Jews. I used them for work in the field. I ploughed, harrowed, sowed grain, brought potatoes in to the pit and hay from meadows, from Wólka. We worked in the field mostly in a team, but there were also such days that I was alone, without supervision. From the side of Milewek, from a distance I saw only the church in Prostyń. I planned to unharness the horses and run away. I wanted to escape to Gródek on the Bug river, because I had cousins there, but when I thought what the Germans could do to my family, I quickly stopped dreaming about escaping. At the end of the summer, after the main harvest, there was still buckwheat left to scythe in the field near Kolonia Socha. I remember that some of us were scything buckwheat, the field was stretching from the road to the forest. At the edge of the forest some mushrooms were growing, withered and dried from the sun. I didn’t know what mushrooms they were, but I remember that I ate three and then I felt a great thirst. We, the scythers, got black coffee to drink, whitened with skimmed milk. I drank half a litre of this coffee and then I lost consciousness. Friends dragged me to the barrack, put me on the plank bed and I didn’t get up for the roll call, I was lying unconscious all night long. There were two pharmacists with us in the barrack. Friends asked them to look at me and say if I would live. They said that I had a very healthy heart and that if I survived until the morning, I would live. In the morning I had such a dream: I dreamt that I was at home, in Sabnie and that I was sleeping in the attic of the barn over the cattle. I woke up and vomited. I threw up everything and in the morning I was rushed to work with others. On 2 August 1943, we were picking up stones in the field and suddenly we heard shots, explosions and saw black smoke from the side of Treblinka II – the Jewish extermination camp. The Ukrainian guarding us ordered us to lay with our faces to the ground. After some time we heard the camp bell and we were driven to the camp to the square in front of our barrack, where we were lying until the evening with our faces to the ground. It turned out that the Jewish uprising broke out. During our stay in the camp, when the wind was blowing from the Jewish camp, we could smell the sweet smell of burning human bodies, which I later saw with my own eyes. Passing by the Jewish camp to get hay to Wólka I saw how human bodies, bones, tibia were burning and how human fat dripped from this special gutter into some tank.

One day I was ploughing the field near Kolonia Socha. There were three of us ploughmen, and the second group of prisoners was covering the roof of the barn with straw. A man from Poznań lived in Kolonia Socha. He had an adult daughter. There were two groups of us. We were guarded by two Ukrainian watchmen. Then the main Ukrainian, oberwachman, came and asked the farmer’s daughter to bring vodka from Kosowo. The girl brought vodka and the Ukrainians drank it. The oberwachman drank the most and he went crazy. He was really steamed up. He couldn’t forgive himself to whom he served. On his way to the camp, he struggled a lot, and watchmen, less drunk, kept him on the cart. During that struggle I fell off the cart and returned on foot to the camp. I also remember eating dinner on a hot day at noon. It was June or the beginning of July. A large group of Jews was brought from the side of the gravel pit, from the direction of the death camp. It was probably the last transport of Jews from the Warsaw ghetto. They had a lot of valuables. Men, women and children. They were ordered to sit down. The Germans gave them coffee to drink, then they ordered them to undress into underwear and fold everything together. Then they were told that they would go to the bath house and then come back. Before the Jews were taken to the “bath house”, Jew Ignacy was brought. He was allowed to choose a Jewish woman as his wife. And he chose a woman with a child. Then they were driven back to the extermination camp and the Germans carried their clothes and valuables in wicker baskets to the sorting area. After the passage of these Jews, torn up and scattered banknotes were lying on the ground. The Jews must have known that this was their last journey.

Part III

After some time in our camp there was probably to be a rebellion organised by Jews, who had access to practically everything, because they worked at all the utility positions in the camp. When building a barrack, they were to make a double top, where they hid a machine gun and grenades. One evening, during the check-up of the guard by the main German, they wanted to start an armed action against the Germans. For unknown reasons it was discovered by Germans or Ukrainians, as a result of which, the same day in the evening, after dinner, a group of Jews together with Ignacy, Arun and others were taken to the forest and shot dead. I don’t know exactly the details of this execution. In the autumn, after potato lifting, I was pulling potato haulms with harrows. A group of prisoners followed us and shaken these haulms. It was near the forest of Maliszewa. The Ukrainian who watched over us lay down on the road with his face to the ground. The prisoners who were shaking the haulms, seeing that the Ukrainian was lying there, fled to the forest in a blink of an eye, which was noticed by a guard from a lookout and who started shooting at them in the woods. I and another prisoner taking care of the horses didn’t even realise that they had escaped, and the watchman only woke up when he heard the shots. It was on Saturday evening. We returned to the barrack and the night passed quietly. The next day, on Sunday, after dinner, Germans and Ukrainians fell into our barrack, shouting, Hands up!. They drove us out to the next empty barrack where we were searched and stripped naked. They were looking for something. They told us earlier to take out everything that we had in our possession. They found four hundred zlotys sewn in the jacket collar of one of the prisoners, Kluczyński from Rogów. They hang him through the rungs of a ladder specially set up and beat him terribly on the back with wooden sticks, so that soon his entire body was covered in bruises. After this incident with Kluczyński I was very afraid, because I had one hundred zlotys hidden in the jacket tail, which I hadn’t reported before. Luckily, however, I found a German farmer, Roten Fir, who probably liked me. He did not order me to strip and he did not search me at all. I was the only one in the barrack that the Germans didn’t search.

There was a period when some prisoners were going to work in the direction of Małkinia, to build some kind of embankment, probably under the railway track. We called it (I don’t know why) the “Waser bank”. This group worked outside the camp and was guarded by Ukrainians and one German. During these work our families did everything to help us somehow, especially by supplying us with food. They contacted people who lived near this “Waser bank”. We first had to bribe the Ukrainians somehow to be able to pass on some parcels or money. This way, the prisoners who worked there could have something to eat and, from time to time, they managed to smuggle something into the barrack. In the group of these workers there was a man whose name I don’t remember. He served as a groupman. This man often brought us money from our families with a piece of paper, what and how much for whom. He smuggled this money in his shoe, under a specially detached sole. Once the Germans organised a search, I don’t know if it was an accidental or intentional search. In any case, they took everything they carried to the barrack, and they found the money on the groupman. They stripped him naked and they found money in the sole of the shoe. They beat this man hard. There was no white spot on his whole body. He was all blue. We were terrified by this sight. Since then, smuggling has become very difficult, but from time to time someone else has brought something. Polish railwaymen were also of great help to the prisoners. Railwayman Stanisław Gawkowski was coming to us, to the gravel pit. He was describing the wagons filled with gravel. He was also bringing us money. We could buy something to eat with the money that someone managed to smuggle to the barrack from those who brought food from “Waser bank”. The camp life from day to day, from week to week was becoming more and more terrible. Great hunger, lice, approaching autumn, rains were coming. I slept on bare planks throughout my stay in the camp, never undressing to sleep. I slept on the upper bed. The roof of the barrack leaked in places so that the water sometimes dripped on the head. We were infested with lice, which practically covered the whole body. Particularly troublesome were the pubic lice, biting the lower abdomen, which was very annoying. Germans, in fear of the typhus epidemic, arranged a steam bath to steam clothes and showers, which we used maybe once a month. After such steaming for some time the lice decreased, but quickly returned with doubled strength. The Germans were very afraid of the typhus epidemic, but in the end, in autumn there was such an epidemic that decimated the prisoners. People were lying on plank beds, in terrible fevers, delirious. They relieved themselves in beds and they died in suffering. Several of my friends died there of this terrible disease. I somehow didn’t get sick, and I ate the leftovers of food from the bowls of sick people. At that time terrible ulcers appeared on my legs because of the cold, boils from ankles to knees, which burst and puss was oozing from them. I couldn’t walk. I joined a group of typhus patients in the back of the barrack. Moreover, other diseases were troubling prisoners in the camp: bloody dysentery, various swellings and many others whose names I don’t even know. No one treated the sick. If someone had a very strong body, they somehow suffered and were either released from the camp in those tortures or died. However, the most terrible thing in the camp was hunger. There was a prisoner called Uhlan in my barrack. I don’t know if it was a surname or he was actually an uhlan. He served a long time in the camp. He carried a rag bag on his back, a backpack in which he kept horse intestines made of fallen horses, brought to the camp kitchen. In his free time he took the end of the intestine out of his backpack and chewed it like a gum. There was also such a situation that a stray cat fell into the camp latrine. The prisoners pulled it out, removed its skin and ate it raw. Despite such terrible hunger, there were also cases where prisoners who smoked cigarettes exchanged the last slice of bread for cigarettes. I also remember another situation in the camp, when three men, Gypsies, who probably were not aware of where they were, were once brought in. They started to run away. The Germans shot at them. One of the Gypsies was wounded, two other were probably killed. Then the German came up to them and trampled them in a puddle of water.

There was a large rotation of prisoners in the camp. Someone was constantly taken away and brought in. Apart from us, from the village of Sabnie, there were also people from neighbouring villages: Hołowienki, Kolonia Hołowienki, Rogów. There was also a large group of men from many other areas of the former Sokołów Podlaski county and not only. There were also people from other parts of Poland. I also remember something else that happened in the camp. It happened during the potato lifting. I carried potatoes to the pit with an iron wagon, a large box with two horses. A pine grove was growing near the camp, which the Germans, no one knows why, were clearing. A large group of Jews, who were clearing these trees and carrying them to the camp grounds, where wood for smoking was chopped down, worked on this job. After this work, when they brought the last trees and cleaned up the area, every Jew was killed with a wooden baton by hitting his head. The Ukrainians did it. At that time, when I was pouring potatoes out of the cart to the pit, the German ordered me to drive to collect those murdered Jews. I drove up and two Jews threw corpses on the cart, and I drove twice to throw them into the hole outside the camp, close to the forest in the direction of Maliszewo. It was a few hundred meters away. On the first cart with corpses a Jew was sitting, half conscious. Blood was leaking from behind his ear after being hit with a stick. This Jew was sitting on a cart full of corpses. He had lowered his legs to the horses, swaying and saying, Mr watchman, I want to live longer, I want to do more. But I drove him to the pit and everyone, including the still alive one, was thrown into it. They were arranged in layers and covered with soil. It was a mass grave, a place where all the corpses from the whole period of existence of the camp were buried. I didn’t know why I was imprisoned in the camp and I didn’t know that in these terrible sufferings I would live to see freedom. However, it happened suddenly without prior notice, I was released in a group of several prisoners before Christmas 1943. Those from Sabnie were released in two groups, a few days apart. My group was released in the evening after steaming in a steam bath. After leaving the camp, we went to the village of Guty, to the village leader. His name was Doliński. They were good people. His wife gave us food and we stayed overnight in their apartment on straw. The next day word was spread to our families and they came to pick us up on a horse cart. The house was filled with joy. Villagers were coming to see us. Slowly I was recovering, eating under the caring eye of my mother.

The account was written down by the son, Jerzy Tomczuk, on 8 March 1998.